N. 25 - Gennaio 2010

(LVI)

Inchtuthil

The meaning of Scotland’s missing capitaL (PArt 2)

di Antonio Montesanti

7.0

Identity

7.1

The

plateau

has

highlighted

the

presence

of

external

settlements.

In

the

case

of

the

‘Women

Know’

tumulus

is

suggested

to

be a

post-Roman

feature.

However,

it

presents

a

cinerary

cist,

dating

in

the

Bronze

Age.

The

main

structure

is

the

prehistoric

ritual

structure

individuated

under

the

fort

and

perfectly

E-W

oriented.

After

the

Romans

had

withdrawn

from

southern

Scotland,

another

little

tumulus

was

erected

on

the

east

counterscarp

bank

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

247-252).

A

similar

situation

has

referred

in

Hayton

where

the

fort

lays

to

few

meters

of

the

ancient

IA

encroachment

(Johnson

et

al.

1978:

58-60,

fig.

2)

(Fig.

12).

The

tough

schematism

of a

fort

could

be

justified

with

the

choice

of

the

site.

The

Romans

could

have

voluntary

superimposed

the

classical

scheme

of a

camp

to a

pre-existent

situation,

seeking

the

sacral

or

divine

support.

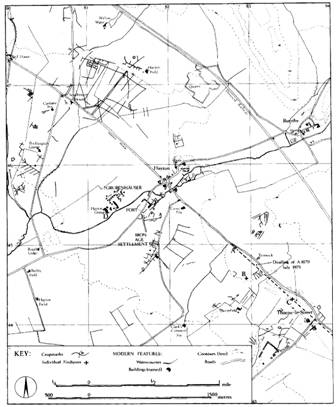

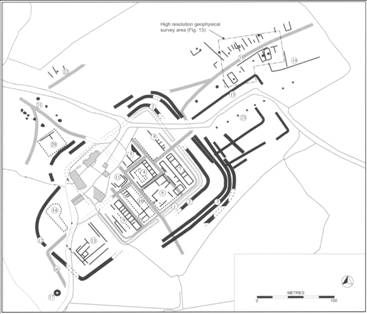

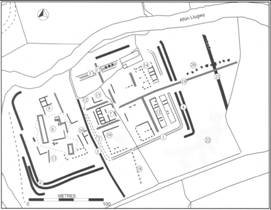

Fig.12

–

Hayton.

External

defensive

ditches

(after

Johnson

et

al.

1978:

59,

fig.

2)

7.2

By

the

few

naturally

fortified

sites

of

Britain,

already

occupied

as

that

of

Brandon

Camp

(Herefordshire),

the

Romans

did

not

adopt

the

square

shape

design,

but

adapted

itself

to

the

previous

native

situation

(Frere

et

al.

1987:

55-59,

fig.

9)

(Fig.

13).

The

same

process

seemed

to

be

in

act

at

Newton

Kyme

(North

Yorkshire)

where

a

vicus

was

enveloping

long

the

main

street

and

around

the

fort,

demonstrating

a

strong

attraction

in

regards

of

natives

(Boutwood

1996:

342,

fig.

7)

(Fig.

14).

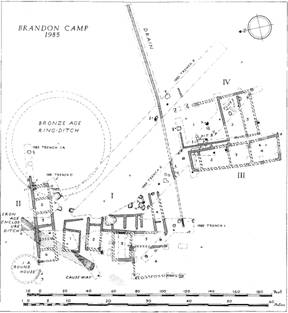

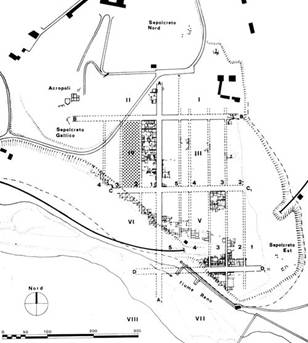

Fig.13

–

Brandon

Camp

BA,

IA

and

Roman

Settlements

(after

Frere

et

al.

1987:

59,

fig.

9)

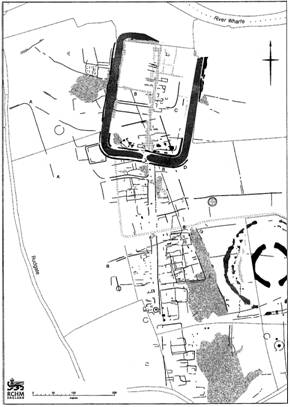

Fig.14

–

Newton

Kyme,

fort

and

vicus

(after

Boutwood

1996:

342,

fig.

7)

A

very

small

example

of

the

transformation

into

a

small

town

can

be

represented

by

Alchester

(Fig.

15)

and

Auchendavy

(Fig.16)

(Sauer

et

al.

1999:

fig.

6;

Keppie

&

Walker

1985:

fig.

1,

photos

A, B),

where

the

modern

structures

are

themselves

superimposed

to

the

ancient

plan

of

the

Roman

camp

and

Cramond

(Edinburgh)

considered

an

attraction

pole

for

the

settlements

around

it

(Fig.17)

(Rae

&

Rae

1974;

Masser

2006).

Outside

of

Britain,

external

enclosures

appear

in

the

Caraş-Severin,

where

it

seems

to

give

the

beginning

to

an

urbanistic

system

outside

the

fort

(Fig.18).

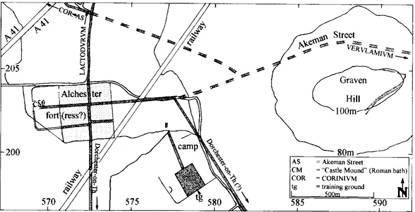

Fig.15–

Alcester,

Roman

military

installations

(after

Sauer

et

al.

1999:

fig.

6)

|

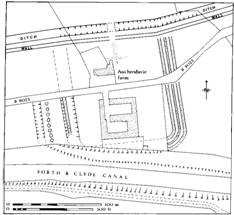

Fig.16 – Auchendavy (after Keppie & Walker 1985: fig. 1) |

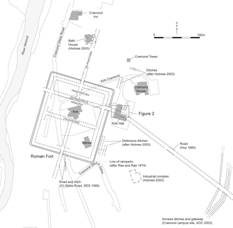

Fig.17 – Alaterva (after Masser 2006: 4, illus 1) |

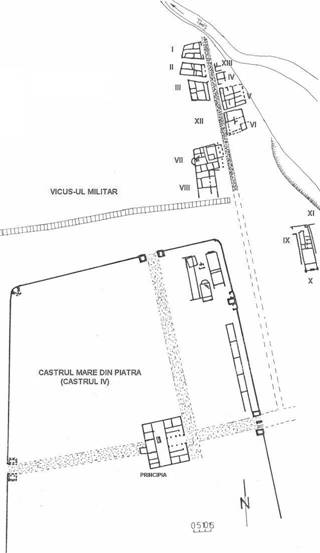

Fig.18

–

Tibiscum.

External

enclosure

(after

Benea

&

Bona

1994)

At

this

point,

we

are

going

to

ask

whether

the

external

structure,

as

the

baths,

were

built

to

prevent

dangerous

situation

due

to

the

fire

or

to

involve

and

influence

the

local

people

to

the

Roman

behaviors

(Tac.

Agr.

21;

Ellis

1995:

103).

8.0

Sacred

The

proceeding

work

to

build

a

Roman

fort

keeps

in

mind

some

main

elements:

The

choice

of a

defendable

location,

the

positioning,

levelling

the

rough

field,

the

sacred

prescriptions

(auguralia)

and

the

rational

or

scientifically

organisation

(Veg.

I,

22;

iii

8.2-3;

Caes.

Civ.,

ii,

25.1;

31.2;

35.4;

Gall.

ii,

17.1;

viii,

7.4).

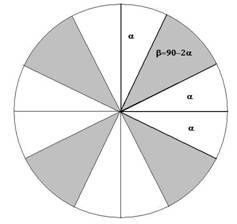

8.1

The

foundation

of a

new

settlement

consisted

of

an

Etruscan

ritual

(Vitr.,

De

arch.

iv.1.9).

The

Augur

was

situated

in

the

centre

of a

large

circle

facing

eastwards,

determining

the

centrelines.

From

here

there

began

two

streets

which,

crossing

in

the

middle,

formed

the

X (deces

–

ten)

from

which

the

decumanus

(or

Via

Principalis)

got

the

name,

oriented

in

East-West

direction

(Sorel

1974:

36).

This

has

been

highlighted

as

the

perfect

centre

of

the

city

of

ancient

Marzabotto

(Fig.19)

where

there

has

been

discovered

a

‘X’

graffito

carved

on a

stone

surface.

(Woodward

&

Woodward

2004:

83,

Fig

4,

C;

Mansuelli

1967;

Mansuelli

1974,

227-251;

289-297).

This

street

crossed

two

raster

fields

with

fixed

designations

showing

as

front

field

and

rear

field:

the

praetentura

and

raetentura

of

the

military

camp,

reflecting

the

quadri-partite

sky

division

on

the

earth

and

becoming

a

“religious

microcosm”

(Helgeland

1978:

1488-1495;

Müller

1961:

22

ff.).

Fig.19

–

Plan

of

city

of

Misa

(from

http://digilander.libero.it/m_sumattone/2003-2004/documenti.htm)

The

fort

was

square

shaped

and

surrounded

by a

ditch,

enclosed

by a

sacred

right-angled

wall.

The

main

public

thoroughfares

crossed

the

centre

of

each

side

through

the

doors.

The

forum,

the

centre

for

all

social

activities,

was

in

the

intersection

of

the

two

axial

streets

and

there

was

located

the

altar

of

the

camping

(augural)

and

the

commander

building

(Fig.20)

(Snodgrass

1990:

57-60).

There

are

reasonable

argumentations

for

the

orientation

of a

Roman

camp

as

‘archaeoastronomical

phenomenon’,

that

seem

demonstrate

scientifically

a

solar

orientation

of

most

of

Roman

forts

in

Italy

(Magli

2008:

67)

(Fig.21).

|

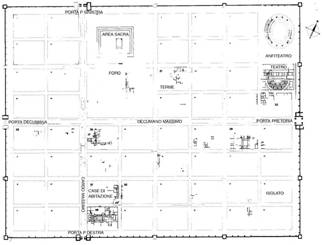

Fig.20 – Orientation of a roman fort (after Snodgrass 1990: 60, fig. 32) |

Fig.21 - Range of the rising positions of the sun in relationship with the axes of a castrum (after Magli 2008: 69, fig. 2). |

The

case

of

Augst

appears

the

most

interesting.

The

decumanus

maximus

had

been

moved

54

degrees

from

North

to

East

and

corresponds

to

the

rising

sun

in

the

summer

solstice.

It

is

the

axis

that

established

E-O

direction

observing

the

raising

sun

in

the

first

day

of

centuriation

(Front.

xxvii,

13;

31,

1.

Hyg.

Grom.

cxvi,

10)

and

it

signed

the

foundation

day

of

the

camp,

fort

or

colony,

as a

distinctive

sign.

Augst

would

have

founded

the

21th

of

June

44

BC (Laur-Belart

1973;

Stohler

1957).

A

relevant

number

of

Roman

camps

became

the

nucleus

of

towns

or

an

extension

of

themselves.

Some

of

these,

as

Ansedonia

and

Timgad

(Fig.22)

(Saumagne

1962a;

Saumagne

1962b)

are

orientated

by

the

cardinal

points

(Carl

2000:

334).

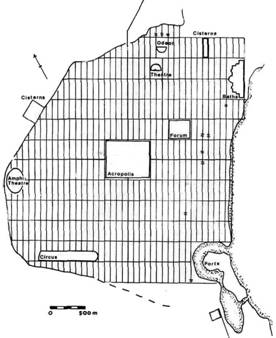

Fig.22

–

Plan

of

the

city

of

Thamugas

(after

Saumagne

1962b)

8.2

Attempts

to

establish

the

orientations

of

Roman

camps

and

forts

by

mathematical

investigations

are

contrasting.

In

one

case,

the

researchers

argues

that

the

orientation

is

non-random

and

so

relied

on

some

form

of

astronomical

observation

(Richardson

2005:

514-426).

In

the

other

contrasting

example,

they

argued

that

this

relies

on a

flawed

use

of

the

Chi-squared

test,

not

an

useful

method

due

to

the

relative

low

number

of

data

sample

(Peterson

2007:103-108).

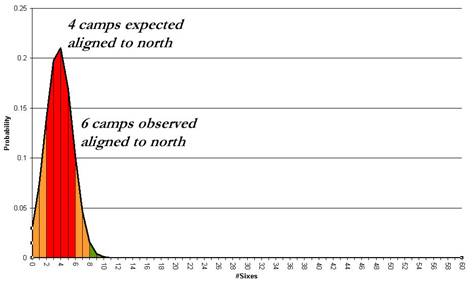

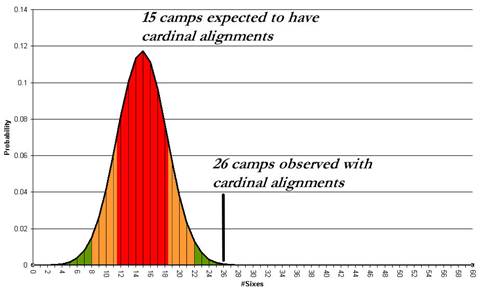

A

third

way

has

tested.

Examining

the

camps

in

England,

using

the

so-called

‘binomial

test’

drawing

two

‘speaking’

conclusion-diagrams

(Fig.23

-

Fig.24).

There

is a

clear

tendency

to

the

orientation

to

the

cardinal

points

which

is

hardly

justifiable

with

strategic

reasons

(Salt

2007;

Magli

2008:

69).

|

Fig.23-Camps aligned to north (after Salt 2007) |

|

Fig.24-Camps aligned to cardinal points (after Salt 2007) |

8.3

The

centre

of

the

entire

enclosure

were

the

principia

or

headquarter,

planned

to

have

a

foreside

reunion

building

with

a

temple

connected

at

the

rear

side

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

79-80).

Here

was

posed

the

shrine

for

the

sacrifices,

where

along

with

the

headquarters

this

became

one

singular

enclosure

delimited

by a

quadrangular

‘fence’

(Pasquinucci:

273-274;

Grant:

299-300;

Milan:

239-249;

Webster:

167-230).

At

Inchtuthil,

this

‘core’

was

the

smallest

known

at

any

legionary

fortress,

even

if

the

shape

seemed

to

be

always

the

same

as

at

Longthorpe,

Pen

Llystyn,

Gelligaer

and

Fendoch,

Chester

and

Caernarfon

(Bowman

1974:

19;

Nash-Wiliams

1969:

157-8;

Richmond

1939:

126;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

95-96,

100)

(Fig.25).

Recent

researches

from

Wales

have

brought

a

new

light

on

the

internal

organisation

of

the

principia.

They

have

in

at

least

three

cases

an

almost

identical

plan

and

similar

dimensions

at

Cefn

Caer

(Fig.26),

Bryn

y

Gefeiliau

(Fig.27)

and

the

identical

Llanfor

(Fig.28)

(Hopewell

2005:

respectively,

229-231

fig.

3;

240-1,

fig.

7;

249-250,

fig.

11).

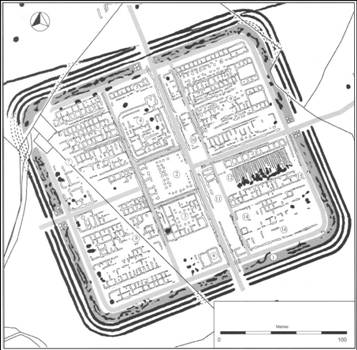

Fig.25

–Different

timber

principia

in

1st

century

forts

(after

Fox

A.

1972:

74

fig.

12)

Fig.26

–

Cefn

Caer.

Plan

and

focus

on

principia

(after

Hopewell

2005:

fig.

3)

Fig.27

–

Bryn

y

Gefeiliau.

Plan

and

focus

on

principia

(after

Hopewell

2005:

fig.

7)

Fig.28

–

Llanfor.

Plan

and

focus

on

principia

(after

Hopewell

2005:

fig.

11)

The

only

fortress

to

have

had

a

similar

extension

of

principia

was

Exeter

(Bidwell

1980:

8-9).

At

the

same

time,

the

orientation

of

the

main

part

of

the

camp,

which

should

convert

the

market

as

in a

hypothetical

colony

as

at

Timgad

(Fig.29)

(Sorel

1974:

36).

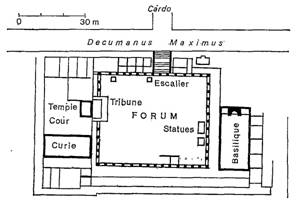

Fig.29

–

Thamugas.

The

forum

area

(after

Sorel

1974:

38)

In

the

centre

of

the

principia

there

has

been

found

a

pit

on

the

same

axis

of

the

enclosure.

It

has

got

argued

that

many

pits

and

well

deposits

known

from

Romano-British

towns

and

military

sites

also

reflect

everyday

ritual

behaviours

at

Newstead

(Clarke

1997;

Clarke

1999:

42)

and

at

Silchester

which

reflect

the

continuation

of

prehistoric

traditions

of

such

ritualistic

and

depositional

behaviour

into

the

historic

Roman

period.

It

is

possible

that

the

same

situation

has

happened

at

Inchtuthil

(Fulford

2001;

Woodward

&

Woodward

2004:

77;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

247-252).

That

was

the

sacred

function,

the

same

of

the

Capitol

in

Rome.

This

identification

could

be

confirmed

by

the

high

podium

of

the

temple

assumed

to

be

behind

the

basilica,

for

the

position

of

the

enclosure

at

the

cross

of

main

streets

and

for

the

presence

of

an

altar

or

‘sacrificial

pit’

in

the

centre

of

the

court

of

the

basilica

as

well

as

attested

at

Nijmegen

(Bogaers

et

al.

1979:

41-2).

9.0

Unholy

9.1

The

main

aim

of

building

a

camp

should

be

that

to

build

a

‘familiar

habitus

(context)’

where

the

soldier

would

feel

at

home

(Veg.

ii,

25.8),

so

that

‘…so

winter

in

them

held

no

fears”

(Tac.,

Agr.:

22,2).

At

Inchtuthil,

that

corresponded

to a

necessity

of

safety,

guarantied

through

eight

probable

granaries,

positioned

near

the

gates

and

explicated

with

an

easier

logistic

easy

supply-function

and

ease

of

distribution

to

the

common

soldier

(Manning

1975:

108;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

117-8;

Richardson

2004:

438).

This

disposition

seems

to

have

the

same

concept

of

those

discovered

in

Valkenburg,

while

in

Britain

one

similar

has

not

yet

found.

For

dimensions,

they

are

comparable

only

to

Exeter.

In

Chester

and

Usk

they

were

grouped

together,

while

the

disposition

at

Bad

Nauheim-Rödgen

or

South

Shields

refers

to

Inchtuthil

(Richardson

2004:

438).

The

hospital

responded

to

the

safety-necessity

of

the

fighters

and

represents

the

most

impressive

structure

of

Inchtuthil

for

position,

precision

of

building

and

for

wideness

(Hygin.

4).

However,

the

hospital

is

smaller

than

that

of

Xanten

and

larger

of

those

at

Neuss

and

Windish,

while

one

similar

seems

to

be

of

Caerleon

(Boon

1972:

76;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

91-96,

100;

Petrikovits

1975:

fig.

27).

9.2

With

all

these

features,

the

camp

was

considered

as

embryonic

colonies

and

models

for

new

city

forms

(Haverfield

1911;

1913;

Laurence

2000:

346-348)

with

the

intention

to

create

an

image

of

Rome

(Owens

1991;

Laurence

1994a).

In

hostile

areas

and

in

period

of

aggression,

the

transformation

of a

Roman

camp

into

a

colony

or a

city

was

a

normal

process

of

the

Roman

system.

The

first

fort

must

be

considered

the

first

colony

of

Rome,

Ostia

in

the

middle

4th

century

BC

(Laurence

1999).

In a

few

cases,

the

strategic

location

seems

to

be

preferred

to

the

sacred

as

Ansedonia

founded

on a

hilltop

and

Sanitja,

where

there

was

built

an

irregular

camp,

not

‘classically’

disposed

(Contreras

2006)

(Fig.30).

Carthage,

after

the

destruction

in

146

BC,

was

built

again

by

the

grid

system

as a

huge

military

camp

(Fig.31)

(Ellis

1995:

93-4,

fig.

7.1).

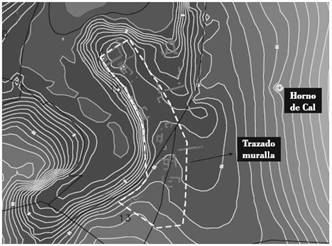

Fig.30

–

The

camp

of

Sanisera

(after

Contreras

2006)

Fig.31

–

Carthago

(after

Ellis

1995:

93-4,

fig.

7.1)

The

Roman

fort-town

became

an

emanation

of

the

Empire

under

the

Julio-Claudian

dynasty

as

at

Aosta

(Fig.32)

and

Torino,

both

bringing

the

name

of

the

first

Emperor

(Magli

2008:

63,

fig.

1).

Fig.32

-

Augusta

Pretoria

(after

Magli

2008:

fig.

1)

The

character

that

set

up

the

colony

of

Osuna

in

the

40s

BC,

provided

detail

of

the

place

of

cosmology

within

the

structure

of

the

city

(Crawford

1996,

393–454)

and

in

the

north-African

colonies

of

Lambèse,

Tebessa,

Djemila

and

Timgad

(Fig.33),

which

represent

the

logical

evolution

from

Trajan

foundation

to

an

amazing

metropolis

(Courtois

1951;

Sorel

1974:

36).

Fig.33

–

Thamugas,

the

colony

as a

fort

(after

Sorel

1974:

36)

The

early

medieval

Barcelona

(Fig.34)

represents

the

‘still

living’

example

of

this

process

(Banks

1984;

Pallares

1972;

Sanpere

1980).

Fig.34

–

Barcino.

Roman

camp

and

its

development

in

the

early

medieval

period

(after

Banks

1984)

Probably

that

is

not

a

case,

whether

in

the

maximal

expansion

of

the

Roman

Empire,

happens

an

osmotic

feedback,

when

the

layout

of

the

Trajan

Forum

conceived

as a

replica

of

enormous

headquarter

(Magli

2008:

70)

(Fig.35).

Fig.35

–

Comparison

between

the

Forum

Trajani

and

the

basic

shape

principia

(after

Magli

2008:

70)

The

temples

and

the

Capitol

were

prominent,

overlooking

the

city,

and

the

walls

provided

defence

following,

after

the

legend,

the

ideal

of

Roma

Quadrata

(Squared

Rome)

arisen

on

the

Palatine.

This

idea

appears

evident

at

Terracina,

overlooked

by

the

monumental

sanctuary

of

Jupiter

Anxur.

The

City

which

contrasted

with

the

egalitarian

ideal

of

the

colony,

evenly

divided

often

on a

level

site,

symbolized

the

false

equality

of

Roman

citizenship

(Laurence

2000:

346-348).

The

representation

of

Rome

as

squaring

city

does

not

have

to

do

anything

with

the

real

townscape,

although

the

cross

in

the

centre

of

the

planned

place

represents

a

symbol

(omphalos

or

umbilicus

terrae:

Müller

1961:

22

ff.)

10.0

Conclusions

Ritual

or

ceremonial

content

appear

to

involve

the

paradigmatic

aspects

of

the

home

city

co-ordinating

this

with

the

political

and

religious

authority.

The

Roman

camp

overtakes

the

astral

conception

in a

functional

conception,

changing

the

meaning

and

the

using

from

a

pure

religious

conception

into

a

real

essence

of

architecture.

However,

the

religious

feature

represents

the

awareness

of

the

Roman

city,

which

is

not

very

different

from

the

sacral

landscape

of

Britain.

The

difference

consists

in

the

envelopment

due

to a

perceived

necessity

for

a

defensive

frontier

strategy

in

response

to

continued

invasion.

The

fort

enveloping

in a

city,

in

Roman

culture,

became

a

metaphysical

items

in

which

the

cives

finds

refuge

and

protection.

It

constituted

a

physical

image,

a

representation

of

ideas,

the

immanence

and

‘collective

imaginary’

of

citizens

of

Empire,

‘understanding

of

the

universe,

centred

ultimately

on

the

city

of

Rome

itself’

(Laurence

2000:

346-348).

|

Modern Name |

Roman Name |

Country |

|

Alchester |

Alchester |

England |

|

Aosta |

Augusta Pretoria |

Italy |

|

Ardoch |

Ardoch |

Scotland |

|

Auchendavy |

Auchendavy |

Scotland |

|

Ansedonia |

Cosa |

Italy |

|

Augst |

Augusta Raurica |

Switzerland |

|

Bacelona |

Barcino |

Spain |

|

Bad Nauheim-Rödgen |

Bad Nauheim-Rödgen |

Germany |

|

Bertha |

Bertha |

Scotland |

|

Bonn |

Bonna |

Germany |

|

Bryn y Gefeiliau |

Bryn y Gefeiliau |

Wales |

|

Caerleon |

Isca |

Wales |

|

Caernarfon in Gwynedd |

Segontium |

Wales |

|

Camelon |

Camelon |

Scotland |

|

Caraş-Severin |

Tibiscum |

Romany |

|

Castillejo |

Castillejo |

Spain |

|

Cefn Caer (Pennal) |

Cefn Caer |

Wales |

|

Chester |

Deva Victrix |

Wales |

|

Cramond (Edinburgh) |

Alaterva |

Scotland |

|

Djemila |

Cuicul or Curculum |

Algeria |

|

Exeter |

Isca Dumnoniorum |

Wales |

|

Fendoch |

Fendoch |

Scotland |

|

Gelligaer |

Gelligaer |

Scotland |

|

Gloucester |

Glevum, Nervia Glevensium |

England |

|

Great Chesterford |

Great Chesterford |

England |

|

Haltern |

Haltern |

Germany |

|

Hayton |

Hayton |

England |

|

Huntcliff Saltburn |

Huntcliff Saltburn |

England |

|

Inverquharity |

Inverquharity |

Scotland |

|

Künzing |

Quintana |

Germany |

|

Lambaesis |

Tazoult |

Algeria |

|

Lauriacum |

Lorch |

Austria |

|

Lincoln |

Lindum Colonia |

England |

|

Llanfor |

Llanfor |

Wales |

|

London |

Londinum |

England |

|

Longthorpe |

Longthorpe |

England |

|

Loudoun Hill (Ayrshire) |

Loudoun Hill |

Scotland |

|

Lympne |

Portus Lemanis |

England |

|

Lyne (Peeblesshire) |

Lyne |

Scotland |

|

Mainz |

Mogontiacum |

Germany |

|

Marzabotto |

Misa |

Italy |

|

Masada |

Masada |

Israel |

|

Miletus |

Milet |

Turkey |

|

Mumrills |

Mumrills |

Scotland |

|

Neuss |

Novaesium |

Germany |

|

Newstead |

Trimontium |

Scotland |

|

Nijmegen |

Noviomagus Batavorum |

Netherlands |

|

Nonstallon |

Nonstallon |

Scotland |

|

Osuna |

Urso |

Spain |

|

Pen Llystyn |

Pen Llystyn |

Wales |

|

Peña Redonda |

Peña Redonda |

Spain |

|

Pesaro |

Pisaurum |

Italy |

|

Petronell |

Carnuntum |

Austria |

|

Regensburg |

Augusta Regina |

Germany |

|

Sanisera |

Sanitja |

Spain |

|

Silchester |

Calleva |

England |

|

Soria |

Uxama Argeala |

Spain |

|

Stirling |

Stirling |

Scotland |

|

Strageath |

Strageath |

Scotland |

|

Strathallan |

Strathallan |

Scotland |

|

Tebessa |

Theveste |

Algeria |

|

Terracina |

Anxur - Tarracina |

Italy |

|

Timgad |

Thamugas |

Algeria |

|

Torino |

Augusta Taurinorum |

Italy |

|

Trier |

Augusta Treverorum |

Germany |

|

Usk |

Burrium |

England |

|

Valkenburg |

Praetorium Agrippinae |

Netherlands |

|

Xanten |

Vetera |

Germany |

|

Windisch |

Vindonissa |

Switzerland |

|

Wroxeter |

Viroconium Cornoviorum |

England |

|

York |

Eburacum |

England |

|

Carthage |

Carthago |

Tunisia |

Tab

3 –

Modern

and

Roman

Names

Correspondences

Bibliography:

Abercromby,

J.,

Ross,

T. &

Anderson,

J.

(1902)

‘Account

of

the

excavation

of

the

Roman

station

at

Inchtuthil,

Perthshire,

undertaken

by

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland

in

1901’,

Proceedings

of

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland

36

(1901-02),

182-242.

Baatz,

D.

(1964)

‘Zur

Frage

augusteischer

canabae

legionis’,

Germania

42,

260-

265.

Banks,

Ph.

(1984)

‘The

Roman

inheritance

and

topographical

transitions

in

early

medieval

Barcelona’,

Papers

in

Iberian

archaeology,

BAR

International

Series,

num.

193,

Oxford.

Benea,

D. &

Bona

P.

(1994)

Tibiscum.

Bucureşti:

Museion

Bidwell,

P.T.

(1980)

Roman

Exeter:

Fortress

and

Town.

Exeter:

Exeter

City

Council

Bogaers,

J.E.,

Bloemers,

J.H.F.

&

Haalebos,

J.K.

(1979)

Noviomagus

: op

het

spoor

der

Romeinen

in

Nijmegen,

Nijmegen

Boon,

G.

C.

(1972)

Isca:

The

Roman

legionary

fortress

at

Caerleon.

Cardiff

Boutwood,

Y.

(1996),

‘Roman

Fort

and

'Vicus',

Newton

Kyme,

North

Yorkshire’,

Britannia,

Vol.

27,

pp.

340-344

Bowman,

A.

K.

(1974)

‘Roman

Military

Records

from

Vindolanda’,

Britannia

5,

360-373

Cagnat,

M.R.

(1913),

L’armée

romaine

d’Afrique

sous

les

empereurs,

Paris

reprint

in

Paris,

1975.

Carl,

P.

(2000),

‘City-image

versus

Topography

of

Praxis’

in:

VIEWPOINT.

Were

Cities

Built

as

Images?

Cambridge

Archaeological

Journal,

10:2,

327-65

(328-335)

Christison,

D.

(1901),

Excavation

of

the

Roman

camp

at

Lyne,

Peeblesshire,

Proceedings

of

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland

35,

1900-1,

154-186

Clarke,

S.

(1997)

‘Abandonment,

rubbish

disposal

and

'special'

deposits’.

In:

TRAC

96:

Proceedings

of

the

Sixth

Annual

Theoretical

Roman

Archaeology

Conference

Sheffield

1996

(eds

K.

Meadows,

C.

Lemke

and

J.

Heron).

Oxford:

Oxbow,

pp.

73-81.

Clarke,

S.

(1999)

‘In

search

of a

different

Roman

period:

the

finds

assemblage

at

the

Newstead

military

complex’.

In:

TRAC

99:

Proceedings

of

the

Ninth

Annual

Theoretical

Roman

Archaeology

Conference

Durham

1999

(eds

G.

Fincham,

G.

Harrison,

R.

Holland

and

L.

Revell).

Oxford:

Oxbow,

pp.

22-9.

Collingwood

Bruce,

J.

(1895),

Handbook

to

the

Roman

Wall.

Ed.

13

by

C.M.

Daniels,

1978,

Newcastle-on-Tyne:

Andrew

Reid

&

Co.

Contreras,

F.

(2006)

‘The

Roman

Military

Fort

at

the

Port

of

Sanitja’,

in:

Historia

de

las

Islas

Baleares,

El

Mundo,

vol.

Nº

16,.

Dudley,

D.R.

(1970)

The

Romans

850

BC -

337

AD,

New

York:

Alfred

Knopf

Ellis,

S.

(1995)

‘Prologue

to

the

Study

of

Roman

Urban

Form’

in

Peter

Rush

(ed.)

Theoretical

Roman

Archaeology:

Second

Conference

Proceedings,

94-10

Fellmann,

R.

(1958)

Die

Principia

des

Legionslagers

Vindonissa

und

das

Zentralgebäude

der

römischen

Lager

und

Kastelle.

Vindonissa

Foster,

S.

(1989) “Analysis

of

spatial

patterns

in

buildings

(access

analysis)

as

an

insight

into

social

structure:

Examples

from

the

Scottish

Atlantic

Iron

Age”,

Antiquity

63,

40-50

Fox,

A.

(1972)

‘The

Roman

Fort

at

Nanstallon,

Cornwall’,

Britannia,

Vol.

3,

pp.

56-111

Frere,

S.S.

et

al.

(1987),

‘Brandon

Camp,

Herefordshire’,

Britannia,

Vol.

18,

pp.

49-92

Fulford,

M.

(2001),

‘Links

with

the

past:

pervasive

'ritual'

behaviour

in

Roman

Britain’.

Britannia,

32:

199-218.

Gillani

G.

(2007),

‘The

Roman

City

of

Uxama

Argeala

(Soria,Spain)

and

its

Study

by

Means

of

Remote

Sensing

and

Digital

Cartography’,

Papers

from

the

XXI

International

CIPA

Symposium,

01-06

October,

Athens,

Greece,

2007,

in

http://cipa.icomos.org

Grahame,

M.

(1999)

“Reading

the

Roman

house:

the

social

interpretation

of

spatial

order”,

in

Alan

Leslie

(ed.),

Theoretical

Roman

Archaeology

and

Architecture,

Glasgow:

Cruithne

Press,

48-74

Grant,

M.

(1974)

The

Army

of

the

Caesars.

New

York:

Scribner's

Helgeland,

J.

(1978)

‘Roman

Army

Religion’,

ANRW,

l1,

Principat,

16.2,

hrsg.

W.

Haase,

Berlin-New

York,

De

Gruyter,

pp.

1470-1505

Hillier,

B. &

Hanson,

J.

(1984)

The

Social

Logic

of

Space,

Cambridge:

University

Press

Hogg,

A.H.A.

(1969)

‘Pen

Llystyn,

A

Roman

fort

and

other

remains’.

Archaeol.

J.

125.

101-92.

Wales,

Gwynedd

Hopewell

D.

(2005),

‘Roman

Fort

Environs

in

North-West

Wales’,

Britannia,

Vol.

36,

pp.

225-269

Johnson

A.,

(1987),

Römische

Kastelle

des

1.

und

2.

Jahrhunderts

n.

Chr.

in

Britannien

und

in

den

germanischen

Provinzen

des

Römerreiches.

Mainz:

Zabern

Johnson

S.

et

al.

(1978),

Excavations

at

Hayton

Roman

Fort,

Britannia,

Vol.

9,

pp.

57-114

Keppie

L.J.F.

&

Walker

J.J.

(1985),

‘Auchendavy

Roman

Fort

and

Settlement’,

Britannia,

Vol.

16,

pp.

29-35

Keppie,

L.

(1997)

'Roman

Britain

in

1996',

Britannia

28,

1997

Konrad,

M.

(2006)

‘Regensburg.

Vom

römischen

Militärlager

zur

mittelalterlichen

Stiftskirche’,

Akademie

Aktuell.

Zeitschrift

der

Bayerischen

Akademie

der

Wissenschaften,

heft

3,

38-45

Laur-Belart,

R.

(1973)

Führer

durch

Augusta

Raurica.

Basel

Laurence,

R.

(1999)

‘Roman

Ostia

Revisited’,

Archaeological

and

Historical

Papers

in

Memory

of

Russell

Meiggs

by

A.G.

Zevi

; A.

Claridge

in

The

Classical

Review,

New

Series,

Vol.

49,

No.

1,

pp.

220-221

Laurence,

R.

(2000)

‘The

Image

of

the

Roman

City’

in:

VIEWPOINT.

Were

Cities

Built

as

Images?

Cambridge

Archaeological

Journal,

10:2,

327–65

(346-348)

Magli,

G.

(2008)

‘On

the

orientation

of

Roman

towns

in

Italy’,

Oxford

Journal

of

Archaeology

27

(1),

63-71

Manning,

W.

H.

(1975)

‘Roman

military

timber

granaries

in

Britain’,

SJ

32,

105-129

Manning,

W.

H.

and

Scott,

I.

R.

(1979)

‘Roman

Timber

Military

Gateways

in

Britain

and

the

German

Frontiers’,

Britannia

10,

19-61.

Mansuelli,

G.M.

(1967),

‘Problemi

e

prospettive

di

studio

sull’urbanistica

antica.

La

città

etrusca’,

Studi

storici,

n.

8,

p.

5-36

Mansuelli,

G.M.

(1974),

‘La

civiltà

urbana

degli

etruschi’

in:

Popoli

e

civiltà

dell’Italia

Antica,

III

Masser,

P.

(2006)

‘Cramond

Roman

Fort:

evidence

from

excavations

at

Cramond

Kirk

Hall,

1998

and

2001’,

Scottish

Archaeological

Internet

Report

20,

2006,

www.sair.org.uk

Milan,

A.

(1993)

Le

forze

armate

nella

storia

di

Roma

antica.

Roma:

Jouvence

Müller

W.

(1961),

Die

heilige

Stadt.

Roma

Quadrata,

himmlisches

Jerusalem

und

die

Mythe

vom

Weltnabel.

Stuttgart:

Kohlhammer.

Nash-Wiliams,

V.E.

(1969),

The

Roman

frontier

in

Wales.

Ed.

By

M.G.

Jarret.

Cardiff

Nissen,

H. &

Koenen,

C.

(1904),

‘Novaesium’,

in

Bonner

Jahrb.

111/112,

1904

Pallares,

F.

(1972)

La

topografia

e le

origini

di

Barcellona

romana,

omaggio

a

Fernad

Benoit,

vol.

IV,

Bordiguera,

Pasquinucci

M.

(1991)

‘I

castra

e lo

sviluppo

urbano’,

in:

Civiltà

dei

Romani

Il

potere

e

l'esercito,

a c.

di

S.

Settis,

Milano:

Electa,

pp.

273-290

Petrikovits

H.v.

(1975),

Die

Innenbauten

römischer

Legionslager

während

der

Prinzipatszeit,

Opladen

Philp

B J

(1977),

The

Forum

of

Roman

London:

Excavations

of

1968-9,

Vol.

8,

1-64

Pitts,

Lynn

F.

and

St.

Joseph,

J.K.

(1985)

‘Inchtuthil:

the

Roman

Legionary

Fortress’,

Britannia

Monograph

Series,

6.

London:

Society

for

the

Promotion

of

Roman

Studies

Rae,

A. &

Rae,

V.

(1974)

‘The

Roman

fort

at

Cramond,

Edinburgh.

Excavations

1954–66’,

Britannia

5,

163–223

Richardson

A.

(2004)

‘Granaries

and

Garrisons

in

Roman

Forts’,

Oxford

Journal

Of

Archaeology,

23(4),

429–442

Richardson,

A.

(2005)

‘The

Orientation

of

Roman

Camps

and

Forts’,

Oxford

Journal

of

Archaeology

24(4).

415-426.

Richmond,

I.A.

et.

al.

(1939),

‘The

Agricolan

fort

at

Fendoch’,

Proceedings

of

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland,

73

(1938-39),

110-54

Salt,

A.

(2007),

The

Orientation

of

Roman

Camps,

in:

www.iscience.wordpress.com/2007/02/17/roman-camps

Sanpere,

M.

S.

(1980)

Topografia

antigua

de

Barcelona.

Barcelona

Sauer

E.

et

al.

(1999)

‘The

Military

Origins

of

the

Roman

Town

of

Alchester,

Oxfordshire’,

Britannia,

30,

pp.

289-297

Saumagne,

Ch.

(1962a)

‘Le

plan

de

la

colonie

Trajane

de

Timgad’,

Revue

Tunesienne

(1933),

p-

35-56;

nouveau

in:

Cahiers

de

Tunisie

10

(1962),

p.

489-508

Saumagne,

Ch.

(1962b)

‘Notes

sur

la

cadastration

de

la

colonia

Trajana

Thamugadi’,

Revue

Tunesienne

(1931),

p.

97-104;

nouveau

in:

Cahiers

de

Tunisie

10

(1962),

p.

509-515

Schörnberger,

H.

(1978)

Kastell

Oberstimm.

Die

Grabungen

von

1968

bis

1971.

Berlin:

Mann

Verlag

Scullard,

H.H.

(1961)

A

History

of

the

Roman

World

753

-

146

BC.

New

York:

Barnes

and

Noble

Shirley,

E.A.M.

(2000)

The

construction

of

the

Roman

legionary

fortress

at

Inchtuthil,

Oxford:

Archaeopress,

B.A.R.

British

series

298

Snodgrass

A.

(1990)

Architecture,

Time

and

Eternity

(2.

Volumes),

Satapitaka

Series

No.

356-57.

New

Delhi

Sorel,

D.

(1974)

‘La

pénétration

romaine

en

Afrique

du

Nord

dans

l'antiquité.

Un

exemple

:

Timgad

jusqu'à

la

mort

de

Empereur

Trajan’

, in

Les

échanges

méditerranéens

.

Paris:

CIHEAM,

1973/04.

p.

35-39

(Options

Méditerranéennes

; n.

18)

Steer,

K A

(1963)

'Excavations

at

Mumrills

Roman

fort,

1958-60',

Proceedings

of

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland,

94,

1960-61,

86-132;

Steer,

K.A.

&

Feachem,

R.W.

(1962)

‘The

excavations

at

Lyne,

Peeblesshire,

1959-63’,

Proceedings

of

the

Society

of

Antiquaries

of

Scotland,

95,

1961-62,

208-218

Stohler,

H.

(1957)

‘Rekonstruktion

des

Vermessungssystems

der

Römerkolonie

Augusta

Raurica’,

Schweizerische

Zeitschrift

für

Vermessung,

Kulturtechnik

und

Photogrammetrie,

n.

12

Walthew,

C.V.

(1988)

'Length-units

in

Roman

military

planning

:

Inchtuthil

and

Colchester'.

Oxford

Journal

of

Archaeology,

7:1,

81-98.

Oxford:

Blackwell

Webster,

G.

(1969)

The

Roman

Imperial

Army,

London

William

Smith,

D.C.L.

(1875),

A Dictionary

of

Greek

and

Roman

Antiquities.

London:

John

Murray.

Woodward

P. &

Woodward

A.

(2004),

‘Dedicating

the

Town:

Urban

Foundation

Deposits

in

Roman

Britain’,

World

Archaeology,

36,

1,

in:

The

Object

of

Dedication

(Mar.,

2004),

pp.

68-86