N. 24 - Dicembre 2009

(LV)

Inchtuthil

The meaning of the Scotland’s missing capital (part 1)

di Antonio Montesanti

1.0

Introduction

The

Roman

fort,

and

particularly

Inchtuthil,

is a

masterpiece

of

regularity

and

ordered

planning.

Its

structure

is

an

enveloped

enclosure,

with

an

apparently

simple

base

which

is

at

the

same

time

extremely

complex.

Its

period

of

use

is

thought

to

have

been

since

the

first

years

of

Roman

expansion

until

the

end

of

the

Empire.

The

forts’

features

correspond

to

fixed

characteristics

between

the

magical

and

the

practical.

It

also

represents

the

ideal

image

of

efficient

and

somewhat

grandiose

protection,

giving

the

perception

for

those

inside

the

fort

a

sense

of

security

as

well

as

maintaining

the

ideals

of a

Roman

city.

|

Alternative Names |

Inchtuthil Plateau |

|

Site type |

FORT |

|

Canmore ID |

28598 |

|

Site Number |

NO13NW 6 |

|

NGR |

NO 1152 3930 |

|

Council |

PERTH AND KINROSS |

|

Parish |

CAPUTH |

|

Former Region |

TAYSIDE |

|

Former District |

PERTH AND KINROSS |

|

Former County |

PERTHSHIRE |

Tab

1 –

Inchtuthil.

Positioning

2.0

Background

2.1

In

AD

83

the

Romans

are

believed

to

have

built

the

legionary

camp

of

Pinnata

Castra

(Ptol.,

Geog.:

ii,

3)

or

Victoriae

(Rav.

Cosm.:

108,

11)

in

the

location

that

we

refer

to

as

Inchtuthil.

This

was

during

the

Roman

expansionist

phase

of

northern

Scotland

and

it

was

abandoned

at

around

87

AD

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

31,

201).

2.2

The

first

excavation

undertaken

of

the

area

was

in

1902

(Abercromby,

Ross,

&

Anderson,

1902:

182-242).

This

was

followed

by a

massive

excavation

of

the

enclosure

fourteen

years

later

(1952-65)

which

revealed

the

plan

of

the

fortress

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

31;

49-56).

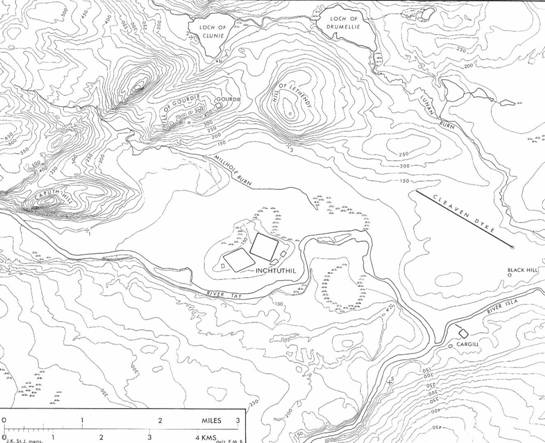

Fig.

1 –

Inchtuthil

fort.

Positioning

(after

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

Fig.

1)

The

fortress

site

lies

on a

fluvial-glacial

bank

south

of

the

Highlands

and

is

cropped

by a

meander

of

the

River

Tay.

The

location

was

of

major

strategic

importance

to

the

Romans

is

it

served

as a

link

between

two

territorial

zones

that

were

pivotal

points

in

maintaining

control

of

the

High-

and

Lowlands

of

what

is

now

Scotland

(Fig.

1,

Tab

1)

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

32).

3.0

Description

(Fig.

2,

Tab

2)

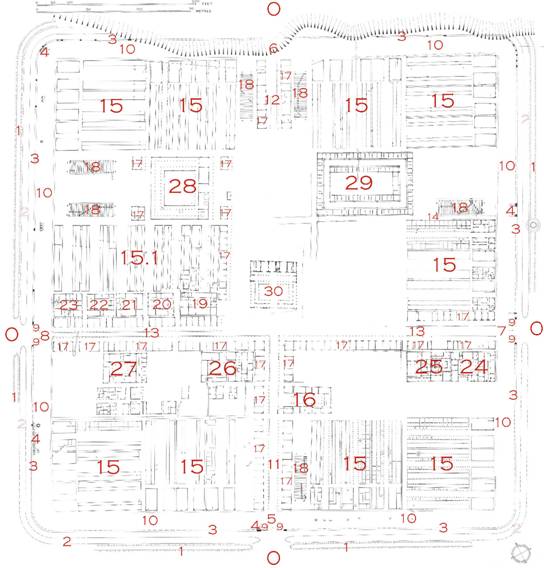

Fig.

2 –

Inchtuthil

fort.

Description

|

0 |

External access point(s) |

INGRESSUM |

|

|

1 |

Ditch |

FOSSUM |

Difensive system |

|

2 |

Primary Rampart (demolished) |

AGGER |

|

3 |

Stone Wall |

VALLUM |

|

4 |

Counterscarp bank |

AGGER |

|

5 |

SW Gate (Porta praetoria) |

PORTA PRAETORIA |

Internal access and connection system |

|

6 |

NE Gate (Porta decumana) |

PORTA DECUMANA |

|

7 |

NW Gate (porta principalis dextera) |

PORTA PRINCIPALIS DEXTERA |

|

8 |

SE Gate (Porta principalis sinistra) |

PORTA PRINCIPALIS SINISTRA |

|

9 |

Tower |

TURRIS |

|

10 |

Sagularis Road or Intervallum |

VIA SAGULARIS SIVE INTERVALLUM |

|

11 |

Praetoria Road |

VIA PRAETORIA |

|

12 |

Decumana Road |

VIA DECUMANA |

|

13 |

Principalis Road |

VIA PRINCIPALIS |

|

14 |

Quintana Road |

VIA QUINTANA |

|

15 |

Cohorts Barracks |

COHORTIS CONTUBERNIA |

Soldiers |

|

15.1 |

First Cohorts Barracks |

PRIMIS COHORTIS CONTUBERNIA |

|

16 |

‘Basilica Exercitationis’ (Workshop?) |

FABRICA? |

Supplies |

|

17 |

Stores |

TABERNAE |

|

18 |

Granaries |

HORREA |

|

19 |

Senior Centurion house (First line) |

DOMUS CENTURIONIS PRIMUS PILUS |

Commanders accommodations |

|

20 |

Centurion house (Prince) |

DOMUS CENTURIONIS PRINCEPS |

|

21 |

Centurion house (Lancer) |

DOMUS CENTURIONIS HASTATUS |

|

21 |

Centurion house (Rear Prince) |

DOMUS CENTURIONIS PRINCEPS POSTERIOR |

|

23 |

Centurion house (Rear Lancer) |

DOMUS CENTURIONIS HASTATUS POSTERIOR |

|

24 |

Tribun’s House I |

DOMUS TRIBUNI |

|

25 |

Tribun’s House II |

DOMUS TRIBUNI |

|

26 |

Tribun’s House III |

DOMUS TRIBUNI |

|

27 |

Tribun’s House IV |

DOMUS TRIBUNI |

|

28 |

Workshop |

FABRICA |

|

|

29 |

Hospital |

VALETUDINARIUM |

|

|

30 |

Headquarter |

PRINCIPIA SIVE AQUILA |

|

|

- |

Praying place |

Auguratorium |

|

|

- |

Learning point |

Schola |

|

|

- |

Reunion centre |

Basilica |

|

|

- |

Temple/ |

Aedes |

|

|

- |

Camp/fort |

Castrum |

|

|

- |

Capitol |

Capitolium |

|

|

- |

Commander's house |

Praetorium |

|

|

- |

Market |

Forum |

|

|

- |

Front field |

Pars antica |

|

|

- |

Rear field |

Pars postica |

|

|

- |

Shrine |

Ara auguralis |

|

Tab

2 –

Inchtuthil.

Description

key

and

translated

features

4.0

Comprehension

4.1

Justified

Accesses

Map

(Gamma

analysis

Map)

(Fig.

3,

Tab

3)

(Hillier

&

Hanson

1984:

82-175;

Grahame

1999:

55-58;

Foster

1989:

44-49)

Fig.

3 –

The

fort

‘system’.

Justified

Accesses

Map

(Gamma

Map)

Fig.

3 –

The

fort

‘system’.

Justified

Accesses

Map

(Gamma

Map)

4.2 The

presence

of a

stone-wall

surrounding

the

fort

postulate

the

project

to

transform

the

fortress

entirely

in

stone

as Nijmegen

and

Chester.

Its

unfinished

state

is

illustrated

by

the

presence

of

such

a

small

headquarter,

the

lack

of a

pair

of

tribunes’

houses,

possibly

two

granaries

and

some

private

accommodation.

Missing

also

is

the

parade

ground,

the

market

and,

above

all,

a

commander's

house,

although

space

was

reserved

beside

or

behind

the

headquarter.

However,

the

hypothetical

envelopment

of

the

structure,

observing

the

two

central

clear

places

and

comparing

that

with

London,

could

comprise

two

markets

(Philp

1977:

37;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

86).

4.3

The

plateau,

on

which

lays

the

most

northerly

legionary

fortress

of

the

Roman

Empire

circumscribes

other

elements

-

The

‘Redoubt’,

the

‘Officers’

‘temporary’

compounds

and

a

stone

bath-house

on

South-East

side,

as

at Cramond

(Masser

2006:

4,

illus

1).

On

the

West

side

this

has

shown

an

attached

rhomboidal

empty

fortified

pitch.

The

maximized

occupation

of

the

surface

demonstrates

the

necessity

to

occupy

and

fortify

the

entire

surface

of

the

plateau.

External

pitches

are

also

present

at

Lyne

(Christison

1901:

166

Fig.7;

Steer

&

Feachem

1962:

211

Fig.2)

(Fig.

4),

at

Hayton

(Johnson

et

al.

1978:

76,

fig.

13)

(Fig.

5)

and

perhaps

recalling

an

evident

intention

to

built

a

twin

fort-camp

connected

with

the

first

one

as

at

Soria

(Gillani

2007:

fig.

3)

(Fig.

6)

and

in

the

similar

Mumrills

(Steer

1963:

86,

fig.

1;

Keppie

1997,

408)

(Fig.

7).

5.0

The

‘defensive

system’

5.1.1

The

positioning

of

the

fort

was

on

three

points:

The

closeness

to

the

river

slope,

the

topographical

strategic

point

of

access

and

ease

of

reaching

the

frontier

line

by

military-way.

The

diagonal

defensive

SW-NE

line

so

installed,

facing

the

Highland

front

by a

system

of

forts

following

the

same

mountain

line,

constituted

a

northern

barrier

imitating

the

formidable

limes

Rhine-Danube,

after

a

different

strategic

conception

based

on a

grid

of

exit-mouth

valleys

and

a

fluvial

system.

Differently

to

that

of

Europe,

in

Britain

the

frontier

was

designed

as a

series

of

fort-lines.

The

southerner

line

was

formed

by

Lyne,

Inverquharity

and

Loudoun

Hill

and

another

one

was

based

on

the

line

Carleon-Chester-York

(Christison

1901:

158

Fig.2;

Steer

&

Feachem

1962:

209

Fig.1;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

44).

5.1.2

The

River

Tay

afforded

three

main

elements

for

a

legionary

camp.

Water-supply,

transportation

and

a

dominant

plateau

on

either

side

of

the

slope

that

provided

a

natural

defensive

position

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

43,47).

The

defensive

project

was

constituted

by a

multi-camps

valleys

control

line,

the

massive

ditch

of

Cleaven

Dyke

situated

East

of

the

fort,

a

timber

breastwork

on

the

West

side

of

the

plateau

and

the

classical

conjunction

ditch

and

wall

made

up

of

stone.

The

strategic

position

of

Inchtuthil

seem

to

be

more

familiar

to

those

of

continental

Europe

as

Nijmegen

and

Mainz

for

the

elevating

place

and

similar

to

Regensburg

(Konrad

2006:

39)

(Fig.

8),

Caraş-Severin

(Benea

&

Bona

1994)

(Fig.

9)

and

Soria

for

the

river

proximity

(Gillani

2007:

fig.

3).

5.2

The

Roman

system

situated

circumvallating

the

Highlands

was

served

by a

main

northwards

road,

whose

existence

has

been

recognised

and

detailed,

starting

from

Camelon

to

Stirling

and

from

Strathallan

by

way

of

Ardoch

and

Strageath

to

Bertha

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

44).

5.3.1

Inchtuthil

is

the

first

Roman

military

establishment

in

Britain

to

have

defences

made

up

of

stone,

derived

from

the

northern

sandstone

quarry-site

of

Gourdie

Hill

(William

Smith

1875:

31;

Collingwood

Bruce

1895:

17).

Those

of

Carleon,

York

and

Chester

were

built

in

the

second

Century

AD.

The

use

of

stone,

in

Continental

Europe,

shows

the

intention

of a

permanent

garrison

or a

long-term

camp,

as

was

the

case

at

Windisch

and

Petronell

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

62).

The

stone

wall

was

not

afforded

of

towers,

even

if

those

which

flanked

the

main

doors

and

a

series

of

regular

pits

identified

by

posts,

revealed

the

presence

as

at

Pen

Llystyn

(Hogg

1969:

figs.

5,

18,

20,

22),

Künzig

(Schörnberger

1978:

Abb.

6,

Beil.

5)

and

Regensburg,

where

they

were

transformed

in

stone

(Konrad

2006:

40,

Abb.

6;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

62)

(Fig.

10).

The

fortress

had

four

considerably

larger

recessed

gates

as

at

Lincoln

but

these

were

much

smaller.

The

best

comparisons

are

represented

by

the

‘L-shape’

gate,

which

is

typical

of

the

big

border

forts

as

Xanten,

Nijmegen

and

Windisch

(Manning

&

Scott

1979:

19f,

figs.

1,

8;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

71,

73,

76).

5.3.2The

stone-wall

included

a

schematic

enclosure

of

doubled-row

barracks

organised

in

horizontal

and

vertical

order

and

fronted

by a

veranda.

The

perfect

subdivision

was

in

ten

barrack-quarters,

one

per

cohorts,

which

is

unusual

and

shows

a

concentrically

idea

of

defense.

Eight

barracks

are

present

at

Nijmegen

and

Tazoult,

thirteen

at

Haltern

and

Valkenburg.

Their

dimensions

are

smaller

of

those

of

Bonn,

Carleon,

Windisch

and

Glouchester

but

larger

than

at

Haltern,

Exeter

and

Neuss.

The

uniformity

of

the

barracks

reflects

an

extreme

sense

of

order

and

organisation

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

151-164).

5.4

Along

the

Via

Principalis,

behind

the

stores,

on a

stripe

was

the

allocation

of

the

tribunes’

houses

and

centurions’

quarters.

Their

small

size

reflected

the

need

to

give

more

space

to

the

common

soldier.

The

tribunes’

houses

and

centurions’

quarters

appear

identical

at

Neuss,

Nijmegen

and

Caerleon

and

for

uniformity

of

plan,

at

Xanten

but

different

at

Petronell.

The

relationship

between

the

headquarters

is

present

in

the

early

fortress

of

Haltern

and

Nonstallon,

while

outside

of

Scotland

at

Masada,

Peña

Redonda

e

Castillejo,

(Fellman

1958:

97;

Cagnat

1913:

499-500;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

138-140;

Richardson

2004:

438).

An

evidently

limited

number

of

houses

within

the

fort

demonstrates

that

not

all

the

high

officers

were

present,

who

could

have

remained

at

Wroxeter

along

(Boon

1972:

33-34).

6.0

Division

of

labour

(Fabrica

&

basilica)

At

least

160

shops

were

situated

long

the

main

streets,

reflecting

the

situation

of

Roman-British

towns,

which

is

typical

of

several

other

main

fortresses.

The

most

indicative

analogy

could

be

considered

with

granaries

and

stores/shops

in

Roma

and

Ostia

(Baatz

1964:

260-1;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

179-180).

The

name

of

‘Basilica

Exercitatoria’

(Veg.,

Ars

Mil.:

ii,

23)

comes

by

the

superimposition

of

an

identical

shaped

building

found

in

Caerleon

and

such

identified.

However,

it

does

not

convince.

Other

similar

cases,

at

Windish,

Lambese,

Xanten,

Neuss

(Fig.

11)

and

Petronell

might

suggest

that

it

could

be a

senior

officer’s

house,

a

place

of

religious

importance,

a

theoretical

learning

point

or a

reunion

centre.

The

most

reasonable

interpretation

is

that

of a

specialist

workshop

combined

with

the

storage

capacity

and

distribution

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

119-127;

Tac.,

Agr.:

22,2;

Petrikovits

1975:

82,

fig.

20;

23,

fig.

6;

Boon

1972:

15).

The

workshop,

with

its

open-plan

(‘Bazartyp’)

had

at

least

four

shops

in

relation

to

it.

It

has

no

size

and

composition

comparison

with

other

well-known

types,

though

the

position

is

common

to

the

other

forts

as

Tazoult

and

Windisch.

The

nearest

example

is

at

Caerleon

which

together

with

Inchtuthil,

represents

an

interesting

regional

(Britannia)

and

chronological

(Claudian-Flavian)

difference

(Petrikovits

1975:

91-2;

Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

106;

113-4).

6.1

Before

the

legionaries

abandoned

southern

Scotland,

withdrawing

south

to

Hadrian’s

Wall,

they

demolished

what

they

had

built

at

Inchtuthil.

Over

seven

tons

of

handmade

(nearly

a

million)

iron

nails

of a

considerable

hardiness

were

buried

on

the

site.

This

has

been

taken

as

an

indication

that

they

could

not

be

transported

during

the

withdrawal.

This

demonstrates

the

possibility

that

this

must

have

been

a

desperate

disappointment

for

the

Romans

to

have

left

such

a

resource

and

probably

for

that

reason

were

found

only

9

iron

tyres

(Pitts

&

St.

Joseph

1985:

110-113).