Erwin Panofsky’s Studies

in Iconology

a critical evaluation

di Ludovica

Fracassi

Erwin

Panofsky was undoubtedly one of the

most influential figures in the

development of 20th

century Art History studies.

Generally regarded as the founder of

the iconological discipline, he was

born in Hannover in 1892 and later

studied in Freiburg and Berlin

before teaching History of Art in

Hamburg, where he met Aby Warburg

and Ernst Cassirer (Cieri

Via 1994, 67). This research

analyses what is widely recognised

as Panofsky’s most significant

contribution: the introductory essay

to Studies in Iconology,

in which the author outlined a

threefold method for discovering the

subject matter of artworks.

Without detracting from the

importance it still holds to this

day, my evaluation will aim to prove

that this system is not as objective

and logically consistent as Panofsky

presented it, and therefore needs to

be applied carefully to avoid

turning images into mere codes whose

true meaning is uncovered by simply

following a set of instructions. The

initial paragraph of my study will

thus address and analyse what I

consider to be the author’s most

problematic arguments, while in the

second one I will discuss Panofsky’s

methodological approach and the

critical response it elicited.

I. Close connections

Although influenced by the cultural

references that had shaped

Panofsky’s academic formation in

Germany, the introductory essay to

Studies in Iconology made its

first appearance in 1939 in the

United States, where the scholar had

emigrated to escape the Third Reich.

This pioneering work therefore

constituted the fascinating outcome

of the convergence between the

cultural heritage of the Weimar

Republic, where art historians and

social scientists worked closely

together (Hart

1993, 535), and the new freedom the

author found in the American

continent, also enabling the

diffusion of Warburg’s ideas

overseas.

Before delving into the examination

of specific topics, it may be helpful

to briefly

summarise the general content of the

text.

Panofsky distinguishes

between three levels of

investigation: a

pre-iconographical description,

an iconographical analysis,

and an iconographical

interpretation in a deeper sense.

Their increasing relevance is

conveyed by using three

substantially different words,

progressing from a simple

description to a proper

interpretation in a process bound to

“start with the visual image of the

material object and work towards

understanding its cultural context”

(De

Vries 1999, 49).

According to the author, the first

stage results in the discovery of

the lowest and most superficial

layer of meaning, the primary or

natural subject matter: this

allows the observer, who relies

exclusively on his practical

experience, to recognise that

the shapes and figures he sees in

the image are meant to illustrate

objects and events. With

the iconographical analysis

then, the previously identified

objects and events are

organised together into stories

and allegories with the aid

provided by the knowledge of

literary sources, thus

constituting the secondary or

conventional subject matter.

Finally, the third level leads to

the intrinsic meaning or

content: through a synthetic

intuition the viewer gains

knowledge of the fundamental

characteristics that qualify an

artwork as the unique product of an

artistic personality situated in a

specific historical and cultural

context.

Due to the fluent argumentative

structure, the system appears at

first rather straightforward,

deceiving the reader into believing

that by using these three levels he

will be able to unveil the meaning

of any work of art. Here lies, in my

opinion, one of the most significant

flaws of Panofsky’s approach: the

excessive simplification of the

instead quite complex materials he

engages with. In this essay I will

particularly address how the author,

in an attempt to present his method

as easy to operate but still

effective and objective, tends to

establish one-to-one relationships

between individual objects and

ideas. This weakness is especially

noticeable in his analysis of both

the second and third level.

According to Panofsky, in order to

conduct an iconographic analysis

we must “familiarize ourselves with

what the authors of those

representations had read or

otherwise knew.” (Panofsky

1939 [1972], 12) This argument

implies that every image refers,

even partially, to a specific

written source which, if known by

the viewer, may grant him access to

the subject of that representation.

The author creates a one-to-one

connection between artworks and

texts, thus laying the foundations

for one of the most severe

criticisms levelled at the

iconological discipline in its later

developments: that it had reduced

images to mere codes, to be read as

written documents.

Ernst Gombrich specifically referred

to this same matter as “dictionary

fallacy,” to indicate that art

historians had too often relied on

certain medieval and modern literary

sources to find exact

correspondences with what was being

depicted (Gombrich

1985 [1972], 11-13). It seems clear,

however, how Panofsky has failed to

adequately consider that texts and

images are not always linked by a

close relationship, and that not all

artworks can be considered

representations of stories and

events as they are narrated in

written sources. This is

particularly evident for landscapes

and still-life paintings, as

acknowledged by the author, but also

for artworks included in the

mysterious category of ad vivum

images, like nature casts.

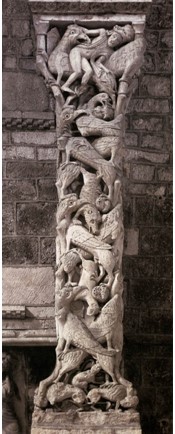

Similarly, Michael Camille used the

sculpted trumeau of the Abbey of

Souillac [Fig. 1] to

illustrate how medieval art too

refers to “somatic rather than

semantic” sources (Camille

1993, 46).

.

.

Sculpted pillar on the inner west

wall, c.1120-1135. Abbey Church

of Sainte-arie, Souillac.

Even in the vast field of

Renaissance art, typically regarded

as more narrative and therefore

favoured by Panofsky’s method, there

are images that bear no relation

with written texts, as in the case

of deschi da parto (birthing

trays): the one painted by Masaccio

and now in Berlin [Fig. 2],

for instance, does not allude to any

specific literary work, but simply

depicts a generic scene of

childbirth.

.

.

Masaccio (1401-1428), Desco da

parto (birthing tray), c.1423.

Gëmaldegalerie, Berlin.

The notion of iconographic

interpretation in a deeper sense

represents the main innovation

introduced by Panofsky’s system: as

I will further discuss in the next

paragraph focused on methodology,

this concept led to a pivotal

turning point in Art History

studies, paving the way for the

development of an in-depth

investigation of the subject.

Although revolutionary, the author’s

suggestion of a tight connection

between artworks and their cultural

background, requires a more careful

evaluation. In this regard, Lyckle

de Vries mentioned how, since

cultures can rarely be considered

consistently homogeneous, artworks

only reflect some of their aspects,

but not their entirety. He wrote:

“When taking the last step in the

application of Panofsky’s method,

great caution is needed, since we

have become aware of the fact that

the relationships between images and

their historical backgrounds are

extremely diversified” (De

Vries 1999, 56). Once again,

then, the problem seems to lie in

Panofsky’s desire to create a close

and exclusive correlation between

different elements. His urge to

connect a work of art to a single

cultural context led him to refer to

the “civilization of the Italian

High Renaissance,” thereby

disregarding the complexity of the

various layers

characterising

that specific milieu, as first

highlighted by Warburg.

II. A new method

As recalled by Michael Holly, in the

early 20th century formal

analyses were the only method

employed to study visual materials,

and “the discipline of art history

was dominated by a preoccupation

almost exclusively with form” (Holly

1984, 24). Alongside Aby Warburg,

Panofsky was amongst the first art

historians who chose to dedicate

their research to the subjects of

artworks and their meaning. Instead

of simply being observed in their

stylistic features, works of art

started to be acknowledged as “the

most eloquent documents of past

cultures,” that had to be understood

as fundamental elements of a broader

context (De Vries 1999, 55). The

transition from a mere description

of images to a systematic discourse

focused on their content was further

emphasised

in 1955, with the renaming of the

third level as iconological

interpretation.

This new methodological approach

received different responses: while

on one hand it was appreciated for

“its vast erudition, the knowledge

of obscure works of art and written

sources,” (McMahon

1940) on the other, nonetheless, it

also attracted considerable

criticism. The main argument raised

against Panofsky’s system,

especially in the United States

where Art History studies were

dominated by Connoisseurship

and the Warburgian tradition was

perceived as completely unfamiliar,

regarded the author’s alleged

disinterest in the formal aspects of

artworks; as mentioned by Claudia

Cieri Via, this idea was based on

the misinterpretation of the opening

line of the introductory essay, and

it resulted in the general belief

that iconographical and iconological

studies were entirely detached from

researches on stylistic and

aesthetic aspects, compared to which

they served a secondary function (Cieri

Via 1994, 113-119).

In a lecture given in 1941 at the

Johns Hopkins University in

Baltimore, the Italian critic

Lionello Venturi thus accused

Panofsky of having isolated form

from meaning in the analysis of

images. He stated: “Here in the

method itself lies the root of the

evil: in fact there is no meaning in

a work of art detached from its

form, as there is no form detached

from its meaning” (Venturi

1941, 66).

A closer evaluation of the scheme

outlined by the German author,

however, reveals that he did study

forms, albeit always as

representations of objects.

Far from excluding stylistic aspects

from his system, Panofsky simply

investigated them for a purpose

distinct from “a formal analysis in

the strict sense of the word”, (Panofsky

1939 [1972], 6-7) and asserted the

impossibility of focusing

exclusively on forms without linking

them to the notion the viewer had of

the items they depicted. By arguing

that “‘Formal analysis’ in

Wölfflin’s sense is largely an

analysis of motifs and combinations

of motifs (compositions)”, the art

historian denied the achievability

of that “vision of pure forms” that

had constituted the core concept of

Purovisibility.

Instead, Panofsky emphasised how

every act of seeing always implies

an act of interpretation as well,

which ultimately represented the

final aim of his innovative approach

to images. In my view, however, it

is worth bearing in mind that

interpretation is unavoidably

characterised by a certain degree of

subjectivity, which the author does

not investigate in its complex

aspects. Therefore, even with regard

to the methodology used to devise

his system, Panofsky faces the same

fundamental issue that, as I have

argued in this essay, represents the

underlying flaw of his approach: a

tendency to oversimplify his

materials in order to purport his

method’s objectivity.

Conclusion

Keith Moxey observed how

“iconology’s currency as an art

historical method belongs to the

past” (Moxey

1993, 27). The critical evaluation

here presented, on the contrary, has

aimed to maintain the unmatched

importance of the introductory essay

to Studies in Iconology for

the history of Art Criticism, while

also acknowledging its weaknesses.

The argument I have attempted to

support is that, although Panofsky’s

pioneering focus on the subject led

to a more complete understanding of

artworks as active evidence of a

culture and allowed to uncover the

mysterious meaning behind certain

representations, the threefold

method he left as a legacy for the

future generations of art historians

lacks complexity. Consequently, an

indiscriminate application of this

system may not always constitute the

most fruitful approach to

analyse

a work of art.

Bibliographical references:

Camille, Michael, Mouths

and Meanings: Towards an

anti-Iconography of Medieval Art

in Iconography at the Crossroads:

papers from the colloquium sponsored

by the Index of Christian Art,

Princeton University, 23-24

March 1990, edited by Brendan

Cassidy,

Princeton University Press,

Princeton 1993,

pp. 43-57.

Cieri Via, Claudia, Nei

dettagli nascosto: per una storia

del pensiero iconologico,

Nuova Italia Scientifica, Roma 1994.

Gombrich, Ernst,

Symbolic Images

[1972],

Phaidon, Oxford 1985.

Hart, Joan,

Erwin Panofsky and Karl Mannheim:

A Dialogue on Interpretation, in

"Critical Inquiry", 19, no. 3 (Spring

1993), pp. 534-566.

Holly, Michael Ann,

Panofsky and the Foundations of Art

History,

Cornell University Press, Ithaca1984.

McMahon, A. Philip, Review of

Studies in Iconology, by

Erwin Panofsky, in "Parnassus",

March, 1940. Moxey, Keith, The

Politics of Iconology, in

Iconography at the Crossroads:

papers from the colloquium sponsored

by the Index of Christian Art,

Princeton University, 23-24 March

1990,

edited by Brendan Cassidy,

Princeton University Press,

Princeton 1993,

pp. 27-31.Panofsky,

Erwin, Studies in Iconology:

Humanistic Themes in the Art of the

Renaissance [1939], Harper &

Row, New York 1972.

Venturi, Lionello, Art

Criticism Now, Johns Hopkins

University Press, Baltimore 1941.

Vries, Lickle de,

Iconography and Iconology in Art

History: Panofsky’s Prescriptive

Definitions and Some Art-Historical

Responses to Them, in

Picturing Performance: The

Iconography of the Performing Arts

in Concept and Practice, edited

by Thomas F. Heck, University of

Rochester Press, Rochester 1999, pp.

42-64.