N. 23 - Novembre 2009

(LIV)

THE BROCH’S COMPLEX OF EDIN'S HALL, BERWICKSHIRE

an ARCHITECTURAL, SPATIAL AND SOCIAL ACCESS ANALYSIS

di Antonio Montesanti

1.

Introduction

The

following

work

looks

at

different

analyses

layers

that

may

be

used

to

understand

the

architectural-social

relation

following

the

principles

of

access

and

spatial

theory

(Hillier

&

Hanson

1984a;

Graham

1999:

51,

Foster

1989:

40-44)

concerning

Scotland’s

most

southern

Broch’s

enclosure

site.

This

site

has

been

the

subject

of

extensive

excavations

in

nineteenth

century

(Turnbull

1881).

The

study

is

based

on

the

resurveyed

plan

by

Dunwell,

mapped

after

the

excavation

of

nine

trenches

in

winter

1996

(Dunwell

1999).

The

essay’s

structure

assesses

the

functional

space

organization

and

the

access

system,

external

and

internal,

allowing

for

theoretical

approaches

to

be

discussed.

2.

Landscape

and

positioning

(1)

The

enclosure

system

lies

at

the

point

where

the

north-eastern

slope

of

Cockburn

Law

(upon

the

summit

of

which

is

situated

a

poorly

understood

and

under-studied

hillfort)

rises

steeply

to

meet

the

Whiteadder

Water,

north

of

Duns.

Other

relevant

elements

are

constituted

by

two

smaller

settlement

places

and

one

disused

copper

mine

(Hoardweel)

along

the

river

(Armit

2003c:

124).

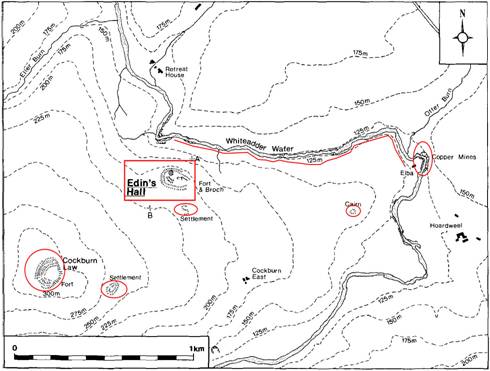

1 -

Landscape

and

remarkable

elements

map

3.

Exterior

and

carrier

access(es)

evaluation

(2)

Two

ditches

draw

an

elliptical

shape

enclosing

a

wide

area

(140m

by

75m)

the

circumference

of

which,

is

interrupted

by

at

least

six

ancient

breaks,

defined

as

entrances

A-F,

(G

is

modern)

(Dunwell

1999:

309).

It

has

been

proposed

that

the

C

break

is a

primary

feature

and

argued

that

the

walled

passage

F

could

be

associated

with

the

settlement

and

passes

through

the

fort

ramparts

to

an

original

entrance

(Turnbull

1857;

Ritchie

&

Graham

1988,

74;

Dunwell

1999:

312).

Those

two

main

entrances

are

each

connected

with

two

focal

landscape

areas.

The

first

one,

probably

the

foremost

(SW),

with

the

hillfort

and

the

second

with

the

mining

zone

(SSE).

However,

there

is

no

justification

that

the

passages

C

and

F

represent

the

only

primary

original

entrances

to

the

fort

(Dunwell

1999:

312).

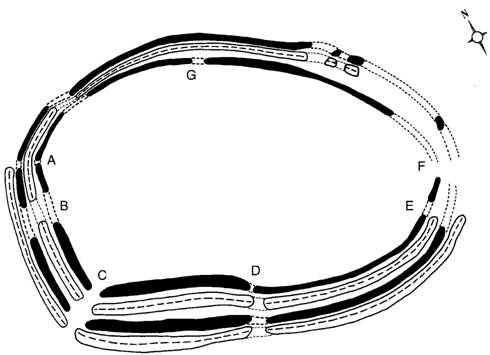

2 -

External

accesses

map

(after

Dunwell

1999:

311)

4.

Building,

depth

and

assessment

of

access

map

(3,

4,

5)

Using

the

definition

by

which

Iron

Age

enclosures

are

qualified

as

“buildings”

(Grahame

1999:

51),

we

have

the

justified

access

map

with

respect

to

exterior

by

system

or

access

(gamma)

analysis

(Hillier

&

Hanson

1984a:

82-175;

Grahame

1999:

55-58;

Foster

1989:

44-49).

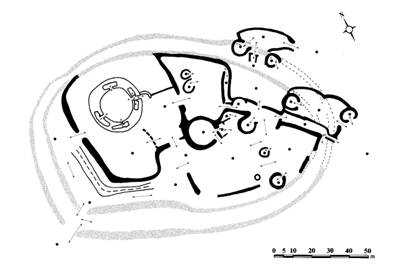

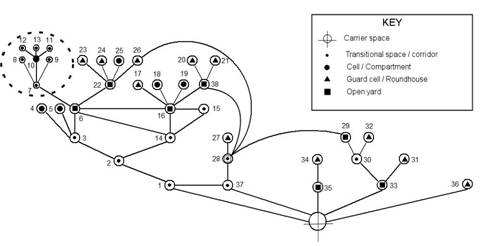

3 -

Posited

access

map

4 -

Unjustified

access

(gamma)

map

superimposed

5 -

Justified

access

(gamma)

map

The

enclosure’s

plan

appears

disorganized,

chaotic,

and

apparently

random.

However,

this

agglomeration

of

structures

responds

to

the

consequences

of

rules

(Fletcher

1977:

49-53;

Grahame

1999:

51).

Considering

the

entire

structure

as a

unique

“social

unit”

(Wallace-Hadrill

1988:

49;

1994:

7),

we

would

deduce

how

the

social

life

was

constituted

(Grahame

1999:

49)

–

contrasting

the

“theory

of

power”

by

which

the

social

life

would

reproduce

itself

(Thébert

1987:

408)

–

with

a

“practical

consciousness”

(Giddens

1984:

41-45).

Although

the

structures

suggested

that

they

are

unlikely

to

relate

to

different

phases

of

use

(Dunwell

1999:

312),

we

can

deduce

that

there

are

two

phases

by

the

spatial

connection

of

the

gamma

analysis

justified

access

map,

if

we

have

established

the

correct

relationships

between

internal

spaces.

We

have

a

central

primary

“core”

of

the

entire

enclosure

which

allows

us

to

recognise

a

first

phase

virtually

and

chronologically

separated

from

other

elements

correlated

with

the

carrier

route

access

(access

map,

left

side).

In

the

structure’s

core

there

seems

be a

wish

to

link

the

entrance

arrangements

(and

the

movement

of

people

through

it)

to

two

transitional

spaces

(3-14)

that

should

lead

up

to

the

broch.

The

broch

itself

represents

the

deepest

feature

of

the

access

points

of

the

enclosure.

Other

transitional

access

points

or

spaces

are

2,

14,

15,

29

and

particularly

37

which

seem

to

have

the

characteristics

and

function

of

corridors.

The

creation

of

large

yards

could

have

had

two

aims.

The

first

taken

together

with

the

other

structures,

might

be

the

staging

or

setting

for

human

action.

The

second

aim

might

have

been

to

create

empty

volumes

of

space

as

well

as

big

storage

places

or a

massive

space

that

might

almost

have

acted

like

a

large

open

meeting

space,

as

“all

human

actions

are

social

actions”

(Hillier

and

Hanson

1984,

1;

Grahame

1999:

51;

Giddens

1984:

375).

The

two

great

yards

present

in

the

core

(6

and

16)

are

connected

directly

by

narrow

accesses

respectively

to

other

two

big

yards

(22

and

38).

5.

Close

and

open

spaces

(focus

on

the

yards

and

roundhouses)

Through

the

Main

Depth

it

is

clear

that

the

two

most

important

yards

are

positioned

in

the

furthest

point

with

respect

to

the

external

accesses

and

than

are

the

less

accessible,

excluding

the

core

broch.

In

the

two

external

enclosures

(ramparts),

formed

by

two

large

yards

(33,

35),

the

roundhouses

seem

have

a

properly

aim.

Indeed,

whereon

the

practice’s

fixation

of

the

prior

broch

phase

have

implied

the

fixation

of

meaning

of

the

precedent

experience

in

reproducing

the

two

new

gateways.

By

observing

the

access

map,

it

does

not

appear

difficult

to

link

the

characteristic

situation

of

the

yards

to

the

Defensible

Space

Paradigm

(6)

or

to

the

open

and

close

cell

scheme

(Newman

1972;

Hillier

&

Hanson

1984b:

6;

Grahame

1997:

146-150).

6 -

Difendible

Space

Paradigm

(Grahame

1997:

139)

Considering

the

big

circumferences

as

the

yards

and

the

little

ones

jointed

as

the

roundhouses,

the

access

analysis

experience

brings

out

the

new

conception

of

roundhouse

as

pure

defensive

element.

The

connecting

spaces

are

each

“controlled”

by

the

circular

buildings

as

well

as

each

of

the

large

yards.

Yard

6 is

directly

controlled

by

the

main

broch,

the

yard

16

only

by

the

bigger

example

of

the

roundhouses

(17),

while

the

yards

22

and

28

represent

obligatory

passageways.

The

boundary’s

concept

features

and

the

building

space

create

its

meaning

through

its

relational

order

Space

Paradigm

or

to

the

open

and

closed

cell

scheme

(Hillier

&

Hanson

1984a:

73;

Grahame

1999:

55).

Examination

of

previously

excavated

roundhouses

seems

repeat

the

broch

experience

as

sub-circular

dry-stone

structure

(36,

31,

34,

30,

27,

20,

21,

26,

23,

stand

by

size

the

n.

17

out).

Those

roundhouses,

except

the

6,

are

present

in

all

the

others

yards

sometime

collocated

in

the

boundaries

(26

e

27),

some

other

times

in

the

middle

of

the

yards

(23,

24

and

20,

21)

and

are

incorporated

in

the

architectural

enclosure;

at

same

time,

they

are

instrument

of

spatial

subdivision

for

the

yards

(16

and

38)

connecting

and

splitting

them.

They

take

the

function

of

'guard

chambers',

and

intramural

cells,

which

are

of

indubitably

exotic

influence

to

the

Tyne/Forth

settlement

and

structural

record

(Dunwell

1999:

347;

Armit

2003c:

123).

6.

Comparison

with

other

similar

systems

(7)

The

roundhouses

enclosure

can

be

reasonably

comparable

demonstrate

the

paragon

with

Atlantic,

such

as

Howe,

Lingro

and

Gurness

in

Orkney

(Ballin-Smith

1994;

Foster

1989:

45-47).

Comparison

with

Gurness

or

Bu

main

round

or

“tower

broch”

structures

(Ritchie

&

Graham

1988:

74;

Armit

2003c:

124;

Foster

1989:

44-45)

is

evident.

However

the

surrounding

enclosure

seems

be

totally

different:

squared

elements

instead

circular

houses

whereon

the

disposition

is

placed

along

a

main

straight

access-way

directly

from

the

access

route

until

the

broch’s

entrance

is

reached.

Moreover

the

complex

structures

are

isometrically

disposed

(symmetrically),

based

on

narrow

and

direct

access

point.

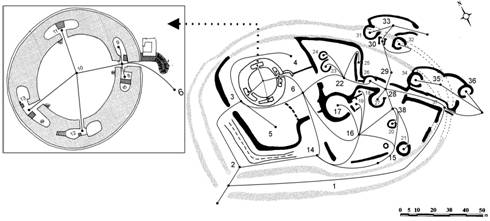

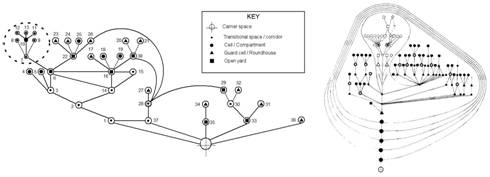

7 -

Comparison

Gurness

and

Edin’s

Hill

gamma

maps

(after

Foster

1989)

We

can

use

the

hierarchical

scheme

of

'broch

towers'

and

compare

the

'Atlantic

roundhouses',

contrasting

the

theory

by

which

they

would

be

such

'substantial

houses'

or

'complex

roundhouses'

(Armit

1990a;

Dunwell

1999:

347).

It

has

been

proposed

that

southern

brochs

were

local

stone

versions

of

'substantial

houses'

incorporating

in

the

Atlantic

roundhouses

enclosures

(Hingley

1992:

27-28;

Dunwell

1999:

351),

can

not

explain

totally

why

such

novel

architectural

forms

were

adopted

at

Edin’s

Hall,

because

most

of

them

appear

isolated

in

the

enclosure.

7.

Relationship

among

enclosure,

buildings

and

landscape

Topographical

and

positioning

comparison

of

broch’s

philosophy

seek

the

necessity

to

find

their

collocation

above

a

terrace

eroded

by a

water-course

or

by

sea

detectable

in

the

northern

Atlantic

above

the

sea

coastal

and

in

the

eastern

Scottish

Borders,

according

to

'scarp-edge'

type

(Christison

1895:

167-9;

Lynn

1895;

Macinnes

1984a:

181;

Dunwell

1999:

309),

in

the

way

can

be

ensure

the

defence

of

one

long

side.

The

building

of

fort

ramparts

and

new

enclosures

located

at

the

northeast

slope

and

with

the

addition

of

two

new

protecting

gates

justify

the

need

to

open

them

on

that

side.

However,

the

creation

of

this

yard

required

the

levelling

of a

sector

of

the

fort

earthworks

(Dunwell

1999:

319).

The

direction

of

the

gates

look

to

the

copper

mine

not

too

far

from

there,

that

could

explain

the

construction

on

this

side,

where

the

roundhouses’

role

and

position

is

connected

with

the

yards.

However,

the

ramparts

are

bounded

to

the

‘core

enclosure’

only

by

one

access,

permitting

so a

major

control.

8.

Findings

Among

the

few

artefacts,

the

most

significant

is

represented

by

the

discovery

of

two

copper

ingots

in

pure

metal

(20

kg

each),

that

explain

the

exploitation

of

the

near

copper

mine.

The

circumstances

of

discovery

are

very

strange.

Only

one

of

the

ingots

is

still

with

us

and

was

found

under

the

stairs

of

one

access

point

of

the

broch

(Dunwell

1999:

338-340;

Armit

2003c:

124).

9.

Structural

and

social

function

Recent

commentators

have

tended

to

argue

that

the

broch

reflects

the

high

status

of

the

personage

or a

pre-eminent

family

through

its

foundation

on a

previously

unoccupied

site,

with

a

later

settlement

developing

around

it (Macinnes

1984b:

236;

Hingley

1992,

28-9;

Dunwell

1999:

351;

Foster 1989:

49).

It

is

not

tenable

that

the

enclosure

structures

have

east-facing

entrances,

following

the

prehistoric

roundhouse

entrances.

Perhaps

they

are

imbued

with

cosmological

significance

(Armit

1997b:

99).

More

than

a

doubt

comes

that

the

broch

was

constructed

as a

status

symbol

reflecting

the

wealth

and

importance

of

its

occupants

in

the

‘centre’

of

which

lived

the

family

(Macinnes

1984a:

192-195;

Hingley

1992;

Dunwell

1999:

348).

The

site

does

not

appear

to

primarily

reflect

considerations

of

defence

due

to

the

lack

of

non-defensive

location,

as

appears

to

be

the

case

at

the

hillfort

above.

That

could

be

disputable,

looking

at

the

circumstances

and

the

positioning

of

ingots

found,

might

lead

us

to

think

and

considering

the

access

map,

the

further

access

point,

is

that

the

ingot

was

laid

in a

hidden

position

perhaps

as a

votive

deposit

(Armit

2003c:

124;

Dunwell

1999:

345).

The

importance

of

the

ingot

is

that

it

represents

the

resource

which

gave

Edin's

Hall

its

wealth.

The

entire

structure

could

have

been

used

to

defend

the

mining

as

well

as

the

control

system

of

the

area,

where

it

could

be a

copper

storage

centre.

10.

Final

considerations

“The

peripheral

position

of

these

structures

may

reflect

an

expansion

of

the

settlement”

(Dunwell

1999:

319).

The

structure’s

enclosure

neither

reflects

a

very

complex

system

nor

a

settlement

system,

since

there

are

fairly

few

house

structures

within

it.

Position,

internal

disposition

and

external

accesses

collocate

like

a

nodal

point

in a

position

of

control

of

production

area

in

the

middle

between

the

hillfort

and

the

mine,

reflecting

an

architectural

system

based

on

resource

exploitation,

storage

and

defence,

where

the

river

become

a

fundamental

element.

Bibliography:

Armit,

I.

(1990a)

(ed.)

Beyond

the

Brochs:

Changing

perspectives

on

the

Atlantic

Scottish

Iron

Age.

Edinburgh,

Edinburgh

University

Press

Armit,

I.

(1997b)

Celtic

Scotland,

London:

Batsford

Armit,

I. (2003c)

Towers

in

The

North:

The

Brochs

Of

Scotland.

Edinburgh:

Tempus

Ballin-Smith,

B.

(ed.)

(1994)

“Howe:

four

millennia

of

Orkney

prehistory”,

in

Soc

Antiq

Scotl

Monogr

Ser,

9

1994,

Edinburgh

Dunwell,

A.

(1999)

“Edin's

Hall

Fort,

Broch

and

Settlement,

Berwickshire

(Scottish

Borders):

Recent

Fieldwork

and

New

Perceptions”,

Proc

Soc

Antiq

Scotl,

129(1),

1999,

303–357

Fletcher,

R.J.

(1977)

“Settlement

Studies

(micro

and

semi-micro)”,

in

David

L.

Clarke,

(ed.),

Spatial

Archaeology,

47-162,

London:

Academic

Press

Foster,

S.

(1989) “Analysis

of

spatial

patterns

in

buildings

(access

analysis)

as

an

insight

into

social

structure:

Examples

from

the

Scottish

Atlantic

Iron

Age”,

Antiquity

63,

40-50

Giddens,

A.

(1984)

The

constitution

of

Society,

Cambridge:

Polity

Press

Grahame,

M.

(1997)

“Public

and

private

in

the

Roman

house:

the

spatial

order

of

the

Casa

del

Fauno”

in

Laurence,

R.

and

Wallace-Hadrill,

A.

(eds.)

“Domestic

Space

in

the

Roman

World

and

Beyond”,

Journal

of

Roman

Archaeology

Supplementary

Series,

No.

22

(1997),

137-164

Grahame,

M.

(1999)

“Reading

the

Roman

house:

the

social

interpretation

of

spatial

order”,

in

Alan

Leslie

(ed.),

Theoretical

Roman

Archaeology

and

Architecture,

Glasgow:

Cruithne

Press,

48-74

Hillier,

B. &

Hanson,

J.

(1984a)

The

Social

Logic

of

Space,

Cambridge:

University

Press

Hillier,

B. &

Hanson,

J.

(1984b)

“Domestic

space

organization:

two

domestic

space

codes

compared”,

Architecture

et

Comportment/Architecture

and

Behavior,

2

(1),

5-25

Hingley,

R.

(1992)

“Society

in

Scotland

from

700

BC

to

AD

200”,

Proc

Soc

Antiq

Scot,

122

(1992),

7-53

Lynn,

F.

(1895)

“Bunkle

Edge

forts”,

Hist

Berwickshire

Natur

Club,

15

(1893-4),

364-76

Macinnes,

L.

(1984a)

“Settlement

and

economy:

East

Lothian

and

the

Tyne/Forth

province”,

in

Miket,

R. &

Burgess,

C.

(eds.),

Between

and

Beyond

the

Walls:

essays

on

the

prehistory

and

history

of

north

Britain.

Edinburgh:

John

Donald,

176-198

Macinnes,

L.

(1984b)

Brochs

and

the

Roman

occupation

of

lowland

Scotland,

Proc

Soc

Antiq

Scotl,

114,

1984,

235-49

Newman,

O.

(1972)

Defensible

Space.

London:

Architectural

Press

Richie,

A.

(1988)

Scotland

BC,

Edinburgh:

HMSO

Ritchie,

A. &

Graham,

R.

1998,

Scotland:

An

Oxford

Archaeological

Guide,

Oxford:

University

Press

Thébert,

Y.

(1987)

“Private

life

and

domestic

architecture

in

Roman

Africa”,

in

Paul

Veyne

(ed.),

A

History

of

Private

Life:

from

Pagan

Rome

to

Byzantium,

Cambridge

Mass.,

Harvard

University

Press,

315-409

Turnbull,

G.

(1857)

“An

account

of

Edin's

Hall,

in

the

parish

of

Dunse,

and

County

of

Berwick”,

Hist

Berwickshire

Natur

Club,

3

(1850-6),

9-20.

Turnbull,

J.

(1881)

“On

Edin's

Hall”,

Hist

Berwickshire

Natur

Club,

9

(1879-81),

81-99.

Wallace-Hadrill

A.

(1988)

“The

social

structure

of

the

Roman

house”,

Papers

of

the

British

School

at

Rome,

56,

43-97